At this year's London Electronic Music Event, we heard how Blawan and Pariah have put together the fiercest live show in techno.

Techno doesn't get much rawer than it does with Karenn. But much like a rock star's expertly crafted bed-head, a lot of care and skill goes into getting things rough around the edges. Arthur Cayzer (Pariah) and Jamie Roberts (Blawan) are both acclaimed solo producers. Before they teamed up they were known for the kind of mutated bass cuts that were everywhere at the turn of the decade. But perhaps more important than the evolution of their musical style is the way their workflow has changed: where before they were both working mostly with software, as Karenn they ditched their laptops in favor of an unruly assemblage of machines. They say they haven't looked back.

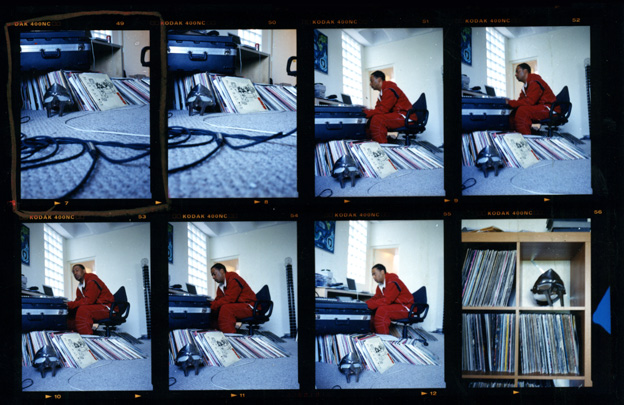

What would count as a comprehensive electronic production studio now comes on the road with them, and it's in the live space that Karenn have really set themselves apart. (They've also released a handful of EPs, primarily through their Works The Long Nights imprint.) So instead of visiting their studio, we invited them to cart their setup to this year's London Electronic Music Event and explain in front of an audience exactly what they're doing among the jumble of boxes and cables. For Karenn, a hardware-based live setup is an exercise in restraint—as much about what it can't do as what it can. After they played a brief but blistering live set, we discussed what they did and how they did it.

Take us through what we just heard.

Blawan: I'm not too sure, actually. Me and Arthur, even though we play together, we kind of—we do our own thing when we're playing. I mean, you notice I'm in this [modular setup], and Arthur's in that over there. We communicate if something's going wrong, or if we want a ride cymbal to go in, but basically we have two different setups. That's Arthur's, this is mine; mine's a little bit more compact than his. Basically we just do our own thing and feed off one another, try and communicate as much as we can. But we found, actually, that we don't really communicate that much.

I was wondering about that, because from my vantage point it really looked like you were both in your own world, but the music was fitting together really nicely.

Pariah: Practice, I think.

Blawan: Practice, definitely practice. I mean, that's kind of the main thing with this whole set—it took us a good year, year and a half to get to a point where we don't have to communicate with each other anymore. Like, I'm totally happy to let Arthur do his thing, and he knows what I'm gonna do, and if he's doing something rubbish then I'll tell him, and vice-versa. You've kind of got to have trust in each other as well.

What you're doing up here—would you say it's largely improvisational?

Pariah: Yeah, I guess when we came in to set everything up, we prepared that little intro thing, and then from then on, after about three or four minutes or so, it's totally improvised. It works better that way.

Blawan: Yeah, it does work better that way. It sounds a bit ropey in parts. I mean, some of that was a bit rubbish, but the good thing about when you're improvising is that you get those really key moments where it all just progresses and then suddenly, naturally, it gels together, you know? They're the more rewarding parts, instead of just pre-programming something that you know exactly how it's gonna sound. We learn from the mistakes, and the mistakes are a good thing, so improvising is key to that.

It sounds like preparation for you guys is really about finding a good place to begin. Tell us about how you find it.

Pariah: I'm not really sure. It's kind of—well, there's a looper here. We make a little thing to loop for the intro. Usually something, like, scary, atmospheric, something like that. Then Jamie usually figures something out on the modular, then really we just go from there. After that, anything goes, really. We do have saved sequences and patterns that we can recall whenever we want, but we don't play tracks. It's funny, sometimes after a set you have people coming up to you going, "What was that track you played?" and it's like, "Well, that's the last time we'll have ever heard that track as well."

Blawan: We've got some sequences saved on the modular, and the [Dave Smith Instruments] Tempest really is the main bass structure, because if not, you can get a bit lost. Me and Arthur kind of keep our heads down, and sometimes it's a little hard to hear everything that's going on because you're so concentrated on your little piece. So to have like a few simple drum beats to build around makes our life a lot easier, really. And there's a bit more substance to the tracks, you know, because with two people improvising purely off all these machines, it would take you a good 20 minutes to get something going that was solid.

Your set is extremely dense with sounds.

Blawan: Yeah, the sound for us is dense, and that's something that we are actually working on. This set isn't perfect at all—it's been a massive learning curve for me and Arthur. Investing what we earned from gigs into this stuff, putting every penny we had into it. Over two years we've managed to accumulate this stuff, and it's been hard work, but over that time we've gotten to know each machine. We've quickly found that yeah, as you said, [the sound we made with them] was dense. There's too much going on, so for us it's just about stripping it back as much as possible, because especially when you're in a club, and they've got, like, 110 dB going through the system, even just a 909 hi-hat feels like a punch in the face sometimes. So you've really got to be careful.

Pariah: We're kind of going through, at the moment, a complete change in the setup, and this is maybe midway through that change, I think. The first shows that we were playing this year, we decided to take a slightly different approach. I don't think we are there yet, but we're kind of getting there. I still think that we've got too much drum stuff, which we are trying to get rid of. Like, we have the 909, which is great, but at the moment the 909 is only being used for its ride cymbal pretty much, and its clap and hi-hat sounds. And to cart something that big around with us is ridiculous. But, unfortunately, it has a very, very good trigger output, which allows the kick drum from the modular to stay in time. So at the moment we need it, but it's playing next to no part in the live show.

Something I noticed is that you have the 909, which is obviously a big classic, but most of the other stuff looks like newer gear. How did you settle on these particular machines?

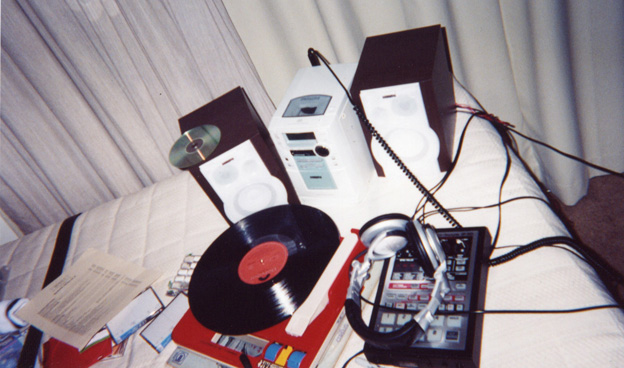

Blawan: Basically, me and Arthur started off very small. We even put together for a £400 sequencer, because when we started we didn't have enough to buy one individually. We gradually earned more money playing these shows, and we just invested it straight away. But the main thing we started off with were the two Tempests. That basically was enough—we could have just toured with two Tempests, really, and that would have been fine. It's more than a drum machine; it's a synth, really. So basically everything started off from the Tempest, and then we just added little bits, like all of what's over there.

Arthur's accumulated most of the little synths. And then I delved into the modular fetish, which has taken over my life a little bit. I mean, it's super complicated and ridiculously hard to get hold of. It's nice as a drum machine, but the possibilities are sort of endless. I'm persevering with it, and hopefully one day I'll have the perfect setup. I'm going a bit off-track here, but basically we started off with the Tempest, a couple of little synths like the Domino, we were using a Moog Slim Phatty for a little bit, which was rubbish, and then I can't remember. The one thing that changed for us was the 909, because originally when we got it we used it a lot, right? It was key, wasn't it?

Pariah: When we first started doing the live shows, they were quite prepared. We'd write tracks and we'd be like, "This one, then this one," and we'd do it on the Octatrack and the Tempest, you can split things into different tracks. After about five or six shows, we found we didn't have the freedom that we have when DJ'ing, it felt very restrictive, and if something went wrong there was nothing we could do about it.

We had one show where some things went wrong, or things weren't working as they should have done, and I found it very, very hard. So, we decided to get a 909, which allowed far more for quick editing of patterns and very on-the-fly drum programming. But actually you can kind of do that with the Tempest, but it's not as easy and hands on with that. As soon as we got the 909, the whole thing changed, and we stopped preparing anything. So we went from preparing everything to preparing nothing!

Blawan: The 909 was the thing that gave us the confidence to be able to tap some 16 beats on there. And it's really, really easy to get something going, to kind of sound like Jeff Mills and not have to worry about it.

This particular 909 has actually been signed by Jeff Mills.

Pariah: I bought it signed, just let me clarify that!

Blawan: Well, Arthur didn't buy it just because it was signed by Jeff Mills. It just happened to be signed by Jeff Mills.

From what you've said of the 909, I get the sense that you're choosing gear not just for the sound but also for how you can use it—how it's functional, how it opens up your workflow.

Blawan: I would actually say that the sound isn't that important, if I'm honest. Functionality is key. If it doesn't function properly in the set and isn't easy to use, then we've got to get rid of it, basically, because there's far too much stuff to bog yourself down with complicated machines. It's kind of the reason why we keep the Tempest as a base structure, because as a live drum machine it's amazing. I would suggest to anyone who's got the money to buy one—immediately go and buy one—because it'll change everything for your setup. But it's also really complicated to do live when you've got flashing lights everywhere, you've got four other synths to think about, a mixing desk and EQing and all the other various things that happen. And watching the people if they actually like the music or not. It's a little bit too much, so we keep that as the base. But everything else we got for pure functionality.

The modular, on the other hand, isn't functional at all. I mean, you've seen me at many a gig looking really frustrated with this thing, but I am determined to persevere with it, because most of the time you have these key bits and it sounds brilliant. You'll never buy a synth that sounds like one really, because it's endless what you can do with it. But functionality or not, this is a complete work in progress for me. I am getting new modules, trying new sequences.

I bought this sort of handmade Japanese sequencer called an [Orthogonal Devices] ER-101, which is basically completely open-ended. It has no sense of bar or anything—you have to input every single parameter, like how long the gate is, how long the bar is, how long the pattern is. It's super complicated, but in terms of modular things it's the most functional thing for me, and that's the reason why I am using it, even though it looks like a pocket calculator. You are trying to write melodies on a calculator screen, which is really difficult, but again this is the exception where the possibilities are far too great to not try and persevere with it.

The oscillator [in the demo] is a Braids, which is a digital oscillator by a company called Mutable Instruments, which do some wicked modules. I was using some analogue VCO oscillators, but I had a few occasions where in a club the heat and the sweat just sent them completely wild, and it just ended up sounding like little girls screaming or something most of the time. So yeah, I've kind of stuck to digital oscillators. I've got a Braids, and then there's another thing called a Morphing Terrarium by Synthesis Technology, and these both are basically wavetable synths. This one has like 256. It's completely sweepable through all the waveforms.

Arthur, have you tried your hand at all with this?

Pariah: No, too daunting for me!

Blawan: Again, like I say, this is a bit of a hobby of mine now. But yeah it's kind of completely taken over everything for me, in terms of my own solo stuff as well. I'm trying to completely reduce my studio to basically just a rack of effects, EQs and modular synths. I'm just trying to write everything purely on a modular, which is great. If you're just wallowing in the studio, just set a multi-track or a stereo recording of it going, record for a couple of hours, and if you want to edit it down on a computer, you've got endless amounts of material there to use.

How close is what you guys are using here to what you would use in the studio?

Pariah: I guess it really depends. I think when we are doing our own solo stuff, we use a mishmash of computer and gear. For a lot of my stuff, I just use the computer. But with the Karenn stuff, we tried recently to start using the computer a little bit, for arranging and mixing down.

Blawan: But it was a bad idea.

Pariah: Yeah, it was a nightmare. So recently we've gone back to recording our tracks live, but multi-track recording them so that we can give them a proper mixdown. The doublepack that we released [Sheworks 004], that was all live recordings but recorded on to one stereo channel—

Blawan: —which was kind of the purpose of that. We wanted that sort of over compressed, grainy, nasty sound. But in the studio with the Karenn stuff, we've tried a lot of different setups, basically, and sometimes, like the last couple of tracks we recorded, we just had the Tempest and the modular, and that was it, and that's kind of all you need as well. You know, there is a lot of equipment on here, but it's because we need diversity. Sometimes if we are playing for an hour or an hour and a half, you ain't got enough there to make it interesting enough, you know? And like I said, that's why the 909 now has gone a bit redundant as well, because essentially, as cool as the 909 sounds, I personally don't wanna hear it for an hour. I can hear the ride cymbal for an hour, but…

You mentioned not having much success bringing a computer into the setup, and that's one of the notable things about what you guys are doing up here: there's no computer. Does anything take its place?

Pariah: The Tempest, probably. In that you can have 16 different beats that you can switch between, and within that—within each beat—you have sixteen, but potentially up to 32 different sounds. I mean, you can pretty much make any sound with the Tempest. It's unbelievable.

Blawan: Sounds like we are really trying to sell the Tempest here. We are not being paid off by these guys! If they wanna give us some free ones, that would be nice [laughs]. But essentially, yeah, the Tempest is a computer. It's not sequencing anything, but it's the backbone.

Pariah: It's got the basslines in it. If there's more pad sounds that we don't want to play on the fly, we've got some stuff stored in there, atmospheric stuff as well. And then some percussion, just to beef things up a bit. As Jamie said, it's a good basis for everything. It leaves you a lot of room to work around it.

So it's taking the place of a dedicated sequencer—like, your Octatrack isn't doing much, is it?

Pariah: Well, I think it's—[brings the Octatrack up on the mixer] it's making this noise, and that's it. The Octratrack is great, but it's got eight channels, or eight tracks in it, yet it only has two outputs. You have to get a decent mix out of the Octatrack alone, which with all this other stuff is nigh on impossible. You can do amazing stuff with it, but I reckon that will be gone within a month or so. We were using it as our clock—I mean, that was its main function, sending the MIDI notes to everything and making sure everything kept in time. But then I recently bought a new thing that does that, and it's about five times smaller.

The centerpiece of all this is the mixer. Tell us about how you're using it.

Pariah: I guess we're not using it as much as maybe we should be. We kind of get everything mixed in the soundcheck. Something that I think we've got to work on more is EQing more on the desk. But really, we get everything ready beforehand.

Blawan: The mix is usually already there, and then the main mixing we do on the actual channel faders is basically just the kick, the bass and really important parts of the music. Any of the details like atmospherics or synths are usually controlled—the volume, anyway—and even a lot of the EQing is controlled directly on the machines themselves and not so much on the desk. Even though there are two of us, we don't split it, so one person is playing the machines and the other is on the desk—which is quite a common thing. Like, one person will usually just stand on the desk. I know quite a lot of live acts that do that.

Pariah: Like Livity Sound. I know there are three of them, but one of them just uses the desk. I think they have quite a big effects chain on the desk, which isn't something that we really have.

In terms of EQing, you said not much of that is happening on the desk but on the individual components of the setup.

Blawan: We have a standard EQ setting. Each channel, we almost instinctively EQ it to what we know the main mix will fit. But then if we do get a soundcheck, obviously we will EQ each channel quite drastically. Like for example, one important thing we've learned is that everything bar the kick and the bass, and even the kick sometimes—we put a 80-Hz cut on it, and really take the bottom off everything, because we found that you really need to be quite drastic with the low cut. Even with the smallest thing, such as a hi-hat, through a system can be really bass heavy. That took us a while to work out—that everything really needs to sit, like you would in a studio.

Pariah: With regards to bass in general, when we first started playing live, it was the one criticism that we heard back from people. So originally we were just using the kick for the bass, and they were like, "It sounds quite pounding in the club, but you're missing that kind of low, like sub-low-end." You know, like the rumble.

Blawan: It was there. But again, you've got to think of it in studio terms, as in each element has to have its own place. We were relying on one thing to cover quite a broad spectrum of the frequency range.

Pariah: So now we have a separate channel for basslines and a channel for the kick.

Blawan: That sounds like a really obvious thing, like it's quite a novice thing to say, but at the time we were just guessing.

I would imagine a lot of people have had this experience in the studio. They put a kick on and don't understand why it doesn't sound like it does on records they're familiar with.

Blawan: Yeah, it's layering. I guess when me and Arthur are writing tracks, sometimes we'll layer up two or three kick drums. When you're playing live and you're asking, "Why is it not full enough?" it's because you've not got that saturation in the bottom end. It wasn't until we started with how the set up is now. We completely overdrive everything below 100-Hz, so there are no transients there, and the dynamic range is squashed. So basically, you've just got this constant rumble. I guess a lot of mastering engineers are doing it by just compressing the low-end, and that was our way of doing it without actually using compression.

You've made the point in other interviews, Jamie, that you guys are not the first live group to be doing techno—that this idea of bringing the studio into the live space has been around for a while. I'm curious who some of your big influences are in putting all this stuff together?

Blawan: I mean, I wouldn't say big influence, but two guys who've sparked my interest really—and it was quite late on—were Octave One. Absolutely amazing live set, purely hardware. I'm not sure how they do it—I'm not sure they improvise fully—but there's definitely some sort of improvisation there. But the main sort of inspiration for me was a couple of guys that go by the name of The Analogue Cops. I started working with them about four and a half years ago now or something. And they work in exactly the same way. They just have pure hardware, record it to tape. They were recording to Betamax at one point.

If you're wanting good saturation, studio tape Betamax is the cheapest, best saturation you can get, really. It's really, really nice, and you can completely re-record over it—apparently, I'm not sure about that—but you know, you can just reuse tapes and it sounds great.

Basically, when I started working with The Analogue Cops, it was purely on hardware, and just going over to Berlin and writing like ten tracks in a day or something. 30 minutes, and you've got something done. Some of them were rubbish, some of them were brilliant.

Being sat at a computer five days a week, or four days a week, I was getting so frustrated. I was using Ableton, and I still use Ableton, but I kind of felt I hit a bit of a dead end with it. I was running out of inspiration, and working with The Analogue Cops—they're called Dom and Marieu—they really opened my eyes. Music doesn't have to be perfection, you know? It doesn't have to be about "that mixdown is sick," sort of how it is in drum & bass a bit. Drum & bass producers are completely obsessed with mixdowns, and I'm completely obsessed with mixdowns, but a good mixdown doesn't mean it has to be a clean or perfect mixdown—it's about how the sound makes you feel. I would have never been able to express myself, however you want to put it, if I hadn't have gone to the studio with these guys. It's not new, but a totally different way for me of writing music.

So for us, they were a massive inspiration. I would go as far as to say they were the main reason why we started this thing, really. They showed us that you don't have to worry about improvising live. The first bit we played today, in my opinion it was rubbish, it wasn't very good. We were a bit stressed out today, you know, so things weren't perfect. But that's fine, you know? I don't have any problems with that. Even if it was just god awful, and no one in this room thought it was any good, I'm just like, whatever, because at the end of the day, you've got an hour to basically do what you want, and that's the whole point of it—that perfection is not what we're looking for; we're looking for nasty, for rough around the edges. That's what makes the music a little bit more special, to me anyway.

When you mentioned Ableton before, I think you were hinting at the downside of the limitless possibilities software like Live offers. I'd imagine the limitations of the Karenn setup allow you to be creative in a way you couldn't be when working the other way.

Pariah: I totally agree with that. So the first record that we did, that was all on the computer. That was before we'd even decided that we wanted to do a live show. We were DJing, and one of the main motivations for doing the live show in the first place was just to separate it from what we do solo, because we both DJ on our own and didn't really see the point of just DJing together. So we started doing the live thing, and then we thought, "OK, why don't we try and convert that into our studio process?" And the speed with which we wrote that doublepack—I mean what, it was like a month or something?

Blawan: I think it was even less than that.

Pariah: We were writing, at some point, like two, three tunes a day.

Blawan: Which some people can do on a computer, but we can't.

Pariah: I can't. I take months.

Blawan: Me and Arthur are really, really slow at writing music, and that's another key point as well. But I think it's a cycle you get yourself into—you procrastinate, and you nitpick and stuff, and the main point is that this totally gets rid of all of that. You're not limited, but you know your boundaries, and if you can work in the boundaries, then you'll work a lot faster. On a computer, like I said, you can do anything.

What is your writing process like now?

Pariah: At the minute, I'll go round to Jamie's house, because he's got all his outboards, EQs and stuff like that. Usually we get the Tempest up and then—

Blawan: —and then press record! It works really in the same sense as what we just did here. Me and Arthur will just spend a couple of hours pressing buttons.

Pariah: Making noises.

Blawan: And then it gels together. Something always gels together with this stuff. Some days we walk away and can be a bit disappointed that we didn't get anything recorded. But at some point you will get something good. It's just a matter of time, and just patience, really. Again, that's completely different from working with a computer, because most of the time, with my experience—and again, probably a lot of people don't have this experience—but a lot of the time the results are not amazing, and it's frustrating.

You mentioned that a big thing for you right now is scaling back your setup. How else is it evolving?

Pariah: It's continually developing. I don't think it will ever get to a stage where we will say, "Right, this is how it is." Ever since we started it's been changing, and there's so much to learn. We're kind of scratching the surface here.

Blawan: Yeah, massively scratching the surface here. If you don't change the machines and swap them—I mean, you've got like a xOxbOx over there, for example. That's basically just a 303 clone. It just sounds like a 303, you know, and that's all you're gonna get out of it. If we don't ever get rid of that one day, then we'll always have an acid patch in the set.

Pariah: But it's our sequencer for my synthesizers at the moment.

Blawan: It's a better sequencer than it is a synth. If we want to carry on playing, having the same kind of sounds or working within these boundaries, then we'll keep everything. But we don't—we want to constantly find new sounds and work with new machines, so we'll constantly be swapping this stuff and seeing what's working. Yeah, at the moment we are trying to find the best way to scale this down, really. I mean, it looks cool and all that, and it looks like you're doing loads of stuff, but essentially what you want to be doing is as little as possible. And that sounds wrong, but it's true, you know? We're using like 20 tracks on the desk, and that's quite a lot for a live set. So yeah, we're basically just trying to make it so everything is quick and easy to use and sort of worry-free, so me and Arthur get to a point where we're not worrying or stressing out before we play.

A lot of the time when we play, we play sort of big festivals, and there's a few thousand people in front of you and you don't have any chance of any soundcheck when you're setting up. A good example is we played in Belgium a couple of weeks ago, and Robert Hood was playing while we were setting up. Arthur's sequencer broke, and we didn't have anything else to sequence with. So Arthur had to quickly try and write some patches on the Octatrack. It's stuff like that. So we are trying to refine it down so we've got a solid sequencer, or a solid synth, that we know is going to be reliable every time. We haven't got to that point yet.

But if you're into gear, there's always something else, right? I mean, it's hard not to lust after something.

Pariah: You know what? For me, I have no idea. I bought this little thing, the Shruthi, the other day, and it's amazing. It cost me 120 quid or something like that. It has quite an uninteresting sound, but it has—

Blawan: Well it's a digital synth with analogue filters in it, basically. And you can get a similar sound with a modular and stuff, because obviously it's a digital synth, but yeah, again, it's—what was the point again?

Everybody: [Laughter]

Blawan: I'm sorry, just a million things streaming through my head at the minute. Like, what machines are we lusting for? I think we've got everything that we wanted to get right now, because everything that we thought that might work perfectly, we went and got it. Same with me with the modular—there's hundreds of modules that I would love to get hold of and try and stuff.

[Looks at Pariah] You've gotta make sure this guy gets out every now and then.

Blawan: I seriously need some sunshine, man! I'm a bit pale and that. It's one of the downsides to doing this stuff.

I actually feel a bit bad—we've spoke a lot about how we play, and I would really love to talk a bit more technical about this stuff. But essentially, what I would like to say is that me and Arthur are not actually experts at all. We've learned this stuff over here by basically—

Pariah: —guessing.

Blawan: Throwing ourselves in the bloody deep end, like massively throwing ourselves in the deep end. And it's actually worked, you know? So I think if anyone is ever tempted to do this or something similar, don't worry about it. The best option is to really give yourself a challenge and just chuck yourself into it, and that's when the best stuff comes out. And if it doesn't work, it doesn't work—no one gives a crap, really, at the end of the day. It's music.

http://www.residentadvisor.net/feature.aspx?2074